Latkes and Hanukah. They go together like coffee and cake or peanut butter and jelly.

Latkes are popularly known as “potato pancakes.” Cuisines around the world have their own versions, like the Irish boxty, Korean gamja-jeon, and Mexico’s tortas de patatas. Let’s be real. Who can resist crispy fried potatoes with seasonings that range from salt, garlic and onion to sauerkraut and cinnamon?

Try eating just one. Impossible.

Latkes are more than just another potato pancake. They’re both delicious and a walk into history. Take one bite and zoom back to biblical times. In those days it was about the oil, not potatoes.

Over 2,000 years ago, the Syrian Greek King, Antiochus IV, outlawed Judaism. He ordered all Jews to worship Greek gods and customs. In 168 BCE, his soldiers seized Jerusalem, massacring thousands of Jews and desecrating the Second Temple. They built altars to Zeus and sacrificed pigs within its walls.

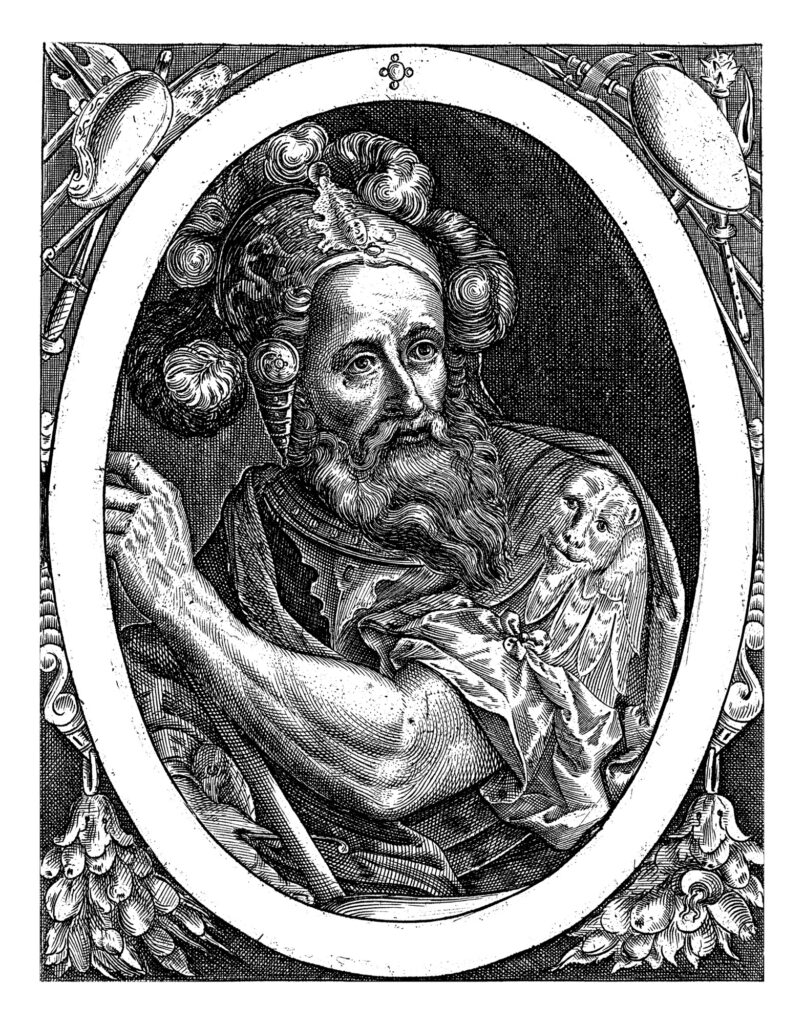

The Jews rebelled, led by Mattathias and his five sons. After his father’s death, Judah Maccabee took over and drove the soldiers out of Jerusalem. They took over the Second Temple. According to History, “they rebuilt its altar and . . . menorah – the gold candelabrum whose branches represented knowledge and creation.”

Judah Maccabee (see below) and his followers rededicated the temple by lighting the menorah with untainted olive oil. They only had enough for one day. The flames miraculously burned for eight days – enough time to get a fresh supply.

Inspired, Jewish sages proclaimed a yearly eight-day Festival of Light.

Today, Jews around the world celebrate the “miracle of Hanukah” by lighting the menorah.

The menorah is one of the best-known symbols of Judaism. It’s on the coat of arms of the State of Israel, seen in synagogues around the world, and the main feature of the holiday of Hanukah. Each day, one additional candle is lit. The ninth candle, or Shamash, is set apart, used to kindle the other candles.

In those days, “candles” were made from wicks placed in oil.

Centuries later, latkes joined the celebration.

Judith was a Jewish widow, known for her beauty and daring. King Nebuchadnezzar of Assyria, sent his soldiers to conquer Israel. They were led by the general, Holofernes. On the road to Jerusalem, they seized Bethulia, Judith’s hometown. Judith believed that the siege was a test from G-d. She used her charm to seduce Holofernes, feeding him salty pancakes filled with cheese. He washed it down with huge amounts of wine until he passed out.

Then Judith chopped off his head before he could kill the Jews.

Oil, cheese pancakes, beheadings, and wine. Who could resist that story?

Renaissance and Baroque artists put it in paintings. (see below). Sculptures were carved.

The story of Judith was related in print – whether true, exaggerated, or great fiction.

That’s up to you.

Either way, latkes and oil were forever linked with Hanukah.

According to Aimee Levitt in The TakeOut, “Jews at various times and places have adapted the ingredients and tools that come to hand for their latkes.”

In the Middle Ages, Italian Jews fried salty cheese (ricotta) in oil to symbolize the Hanukah miracle and the story of Judith.

Spanish Jews fleeing the Inquisition ate cassola – fried cheese latkes.

Ashkenazi Jews (living in Central Europe and eventually migrating to Eastern Europe) ate latkes made with buckwheat and rye.

During the mid-1800s there were crop failures in Poland and Ukraine, leading to mass planting of potatoes. Inexpensive and filling, potatoes became an important part of Ashkenazi Jewish cuisine – inevitably making their way into latkes.

Like the latkes we know today.

Kyle Grace Mills wrote in Food History, “one constant throughout the history of latkes is its reliance on frying and oil. All other adaptations were made with an eye toward economy, availability, and of course, flavor.”

Today you find latkes year-round, mostly made with potatoes, Ashkenazi-style. Many dip them in applesauce or sour cream. They’re a must at Hanukah celebrations: eight days, eight candles, eight gifts, and latkes.

Takeout described Hanukah and latkes as “an active attempt to bind together a community, and assert a cultural identity at the exact time when the majority [Christmas] is most thrown in your face.”

Israelis eat latkes, along with sufganiyat – deep-fried Hanukah donuts. More about that next week. In the meantime, think Judah and Judith. Feast on history with oil and latkes.

It’s so yummy!

What a fascinating history! This is one of the most intriguing food histories I have read. I would imagine Holofernes is probably the only person ever to not be a fan of latkes, for understandable reasons. But the rest of us can certainly enjoy! Thank you for a really fascinating look into this particular history.