They started out as scraps for cattle. Now 70 million pounds of tater tots are eaten every year by people. How did that happen?

Let’s go back to mid twentieth century. Times were rough – the Great Depression had been followed by World War Two. There were shortages, rations, and struggles to make ends meet. Mormon brothers Nephi and Golden Grigg grew up during those tough times. They survived by growing potatoes and corn on their Idaho farms – like most of their neighbors. The brothers lived by the proverb, waste not, want not.

By 1951 things changed. Prosperity returned. Frozen produce was in demand. Americans bought 800 million pounds of frozen foods in 1945-6 alone. The Grigg brothers wanted in.

French fries ruled the frozen potato market. Nephi saw his chance.

The brothers mortgaged their farms and converted a flash-freezing plant in nearby Oregon to a potato processing facility. The goal was to cash in on the booming frozen French Fries market. The machines separated the evenly-sliced fries from leftover scraps of potato.

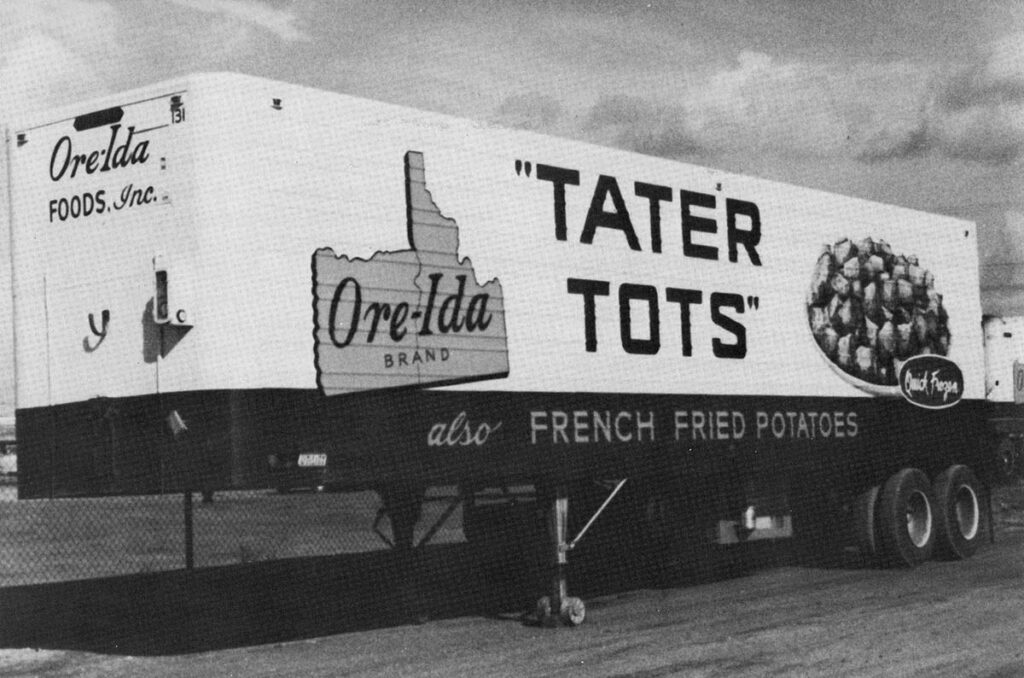

They set up a new company called Ore-Ida. Sound familiar? It stood for their two locations – Oregon and Idaho. Ore-Ida quickly became one of the country’s top producers of frozen corn and potatoes. One issue plagued Nephi. Remember waste not, want not? There was too much waste.

According to Brent Furdyk in The Untold Truth of Tater Tots, the brothers’ goal was to salvage “products that have been purchased from the growers, stored for months . . . trimmed of all defects only to be eliminated into the cattle feed.”

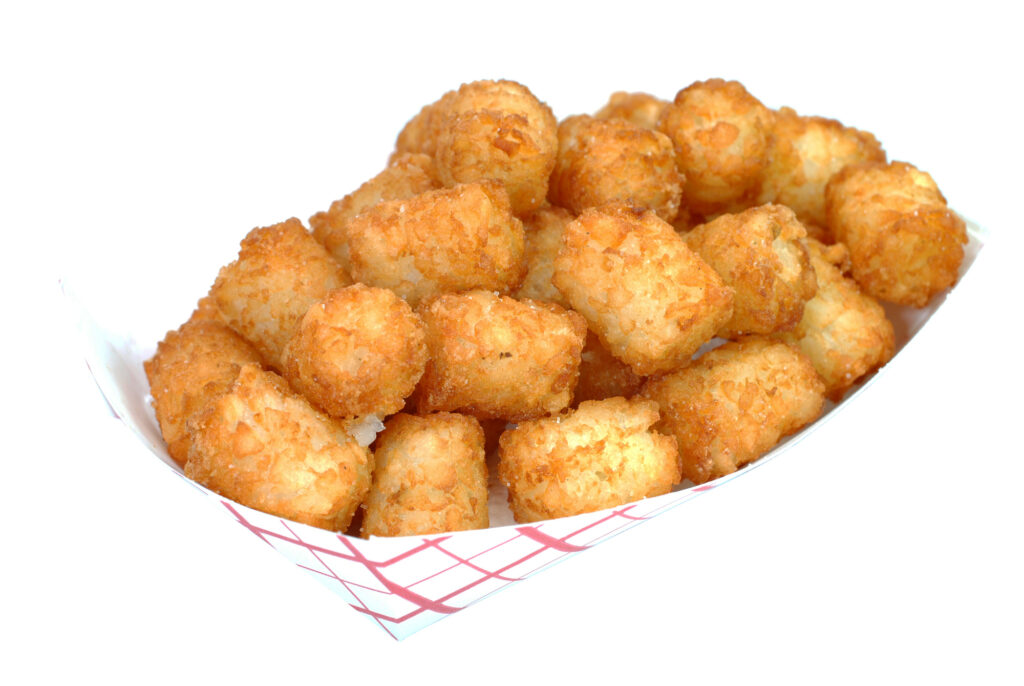

The brothers gathered the potato scraps, mashed them, added seasonings, and forced them into small cylinder shapes. They fried the pieces, and the results were delicious – the 1953 birth of what would become one of America’s favorite comfort foods.

Simply put, scraps for . . . people.

Sorry cattle.

They needed to come up with a good name. The Grigg brothers held a contest for their employees and friends. What should the new-style potatoes be called? A young housewife, Clora Lay Orton, won the contest (helped by her already famous name). She called them “tater tots” – tater was slang for potatoes and tot referred to their small size.

In the beginning, tater tots were cheap. After all, they were made from scraps. People saw them as worthless because the price was so low.

Nephi took matters into his own hands. At the 1954 National Potato Convention he convinced the chef to cook up 15 pounds of tater tots. They were placed in small bowls and distributed as sample foods. “[They] were all gobbled up” really fast,” Nephi wrote later.

The price was raised, and people started buying.

Today, tater tots are an icon in American cuisine. Picky kids love them. Families can’t get enough. Four-star chefs make their own versions. New varieties were introduced, and creative chefs take advantage of their adaptability.

Suddenly there were hamburger tater tot casseroles, breakfast bakes, loaded skewers, and totchos. There were so many imitators that in 2014 Ore-Ida launched an advertising campaign against the “imi-tators.” The message was to “insist on the original . . . often imitated, never duplicated.” The imi-tators always lost because “spud-puppies” can’t compare to the real thing.

Tater tots were so popular that the brand name became a generic term!

Ore-Ida tater tots now come in six flavors. Countries use different names: Canadians eat tasti taters; Australians munch on potato gems or potato pom-poms; and Brits use the formal potato croquettes.

Tater tots are wildly adaptable. For example, according to The Secret History of Totchos, Jim Parker’s unique tater top recipe went national. Parker was in charge of the menu at Oaks Bottom Public House in Portland. He topped tater tots with cheddar and jack cheese, chopped tomato, jalapenos, black olives, red onion, sour cream, and salsa in a humongous serving. “I hated the way tortilla chips got all soggy,” Parker explained.

Totchos beats nachos.

Celebrate National Tater Tot Day in February, chow down on totchos, or DIY.

You can’t go wrong.

Brilliant! Who knew the humble tater tot had such an illustrious history?? Not to mention being delicious- and I’m sure quite healthy for you…! Once again you write a superb article that is fun, informative and appetite-inducing!

Tater Tots! As a teen, I would make tater tots, put in a big soup bowl, and wait for it…a bottle of Turkey gravy, mixed with ketchup & drizzled on the top. If I had the ingredients around, I would make it now. I love this blog explaining the who, what, where and why of our everyday foods.